Great historical fiction doesn’t rely on surprise reveals to keep you turning pages; it lets the place apply pressure until a character must change. In this story, setting isn’t wallpaper—it’s the engine. New York sets the tempo, Le Havre draws the line, the Atlantic teaches presence, and Spain demands consequence. Plot happens because place insists.

Some stories chase spectacle; this one tracks responsibility. Its quiet thesis is demanding and straightforward: spectators keep notes; witnesses keep scars. In a decade when headlines outran certainties, the protagonist learns that truth isn’t a viewpoint you hold at a distance—it’s a place you stand, and standing there costs.

Language doesn’t just describe a world; it decides where you stand in it. In this story, Spanish begins as a set of drills—verbs to conjugate, nouns to file away, basic phrases for buying time in rooms where the questions come fast. But the further he travels, the more language stops being a toolkit and starts becoming a backbone. What begins as a study plan grows into a stance.

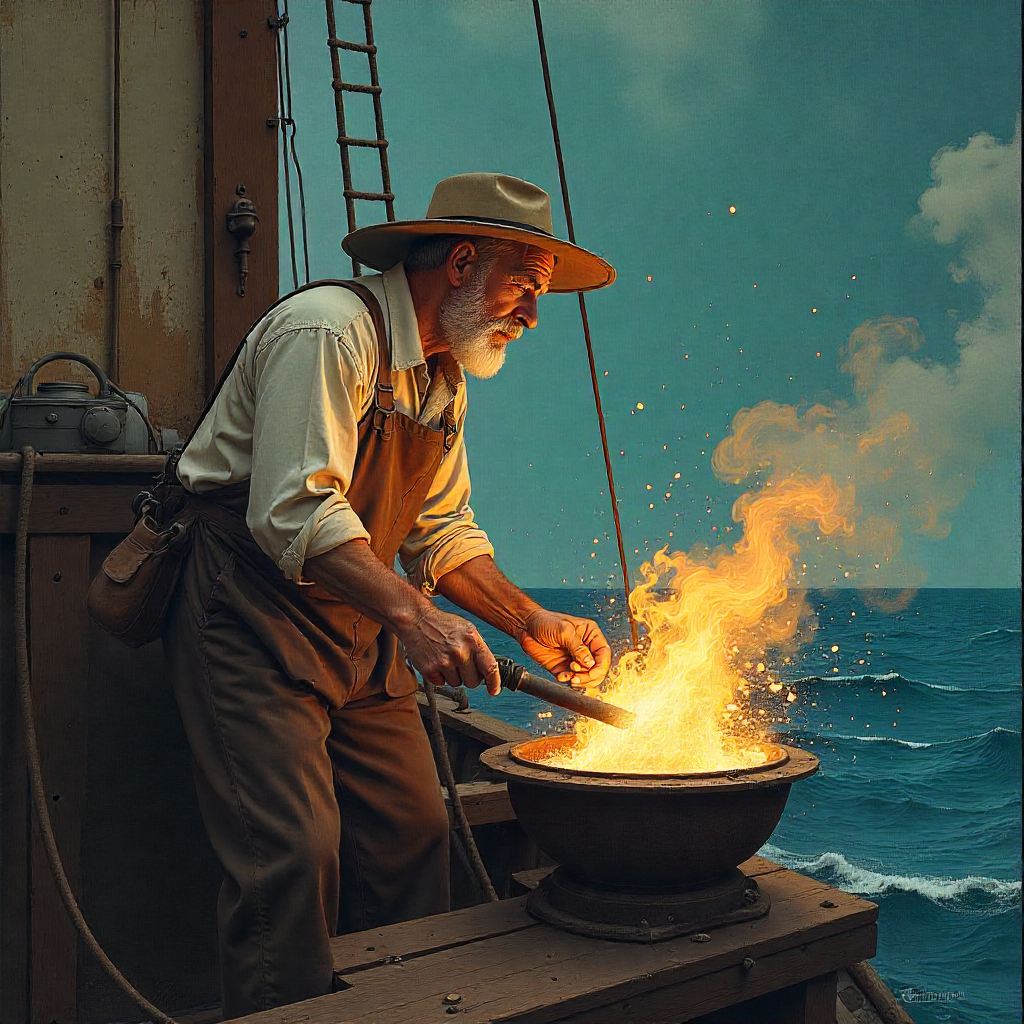

A ticket, a rough sea, and a border that asks for more than papers—those are the first tests. By the time Europe’s headlines harden into wind, the observer has learned the price of presence. He pays it in steadiness: fewer words, firmer steps, and choices that stop asking for applause and start asking for proof.

On the Precipice of the Labyrinth is shaped by the conviction that truth rarely arrives on scene. It arrives afterward, carried in by distance, reconsideration, and the slow editing of memory. The first sentence, “It is important that I tell my story”, signals a narrator who understands that telling is a craft formed by time, not an impulse triggered by spectacle. The choice of Miguel de Unamuno for the epigraph, “Suffering is the substance of life and the root of personality”, tightens this ethic: experience acquires meaning only when endurance has tempered it. This is not a book of dispatches; it is a book of testimony.

In On the Precipice of the Labyrinth, Spanish is not a souvenir gathered en route to Europe; it is the instrument that tunes attention, dignity, and moral readiness long before ports or borders appear. The novel traces a language apprenticeship that begins on ordinary car rides and matures into professional vocation, turning words into wayfinding.

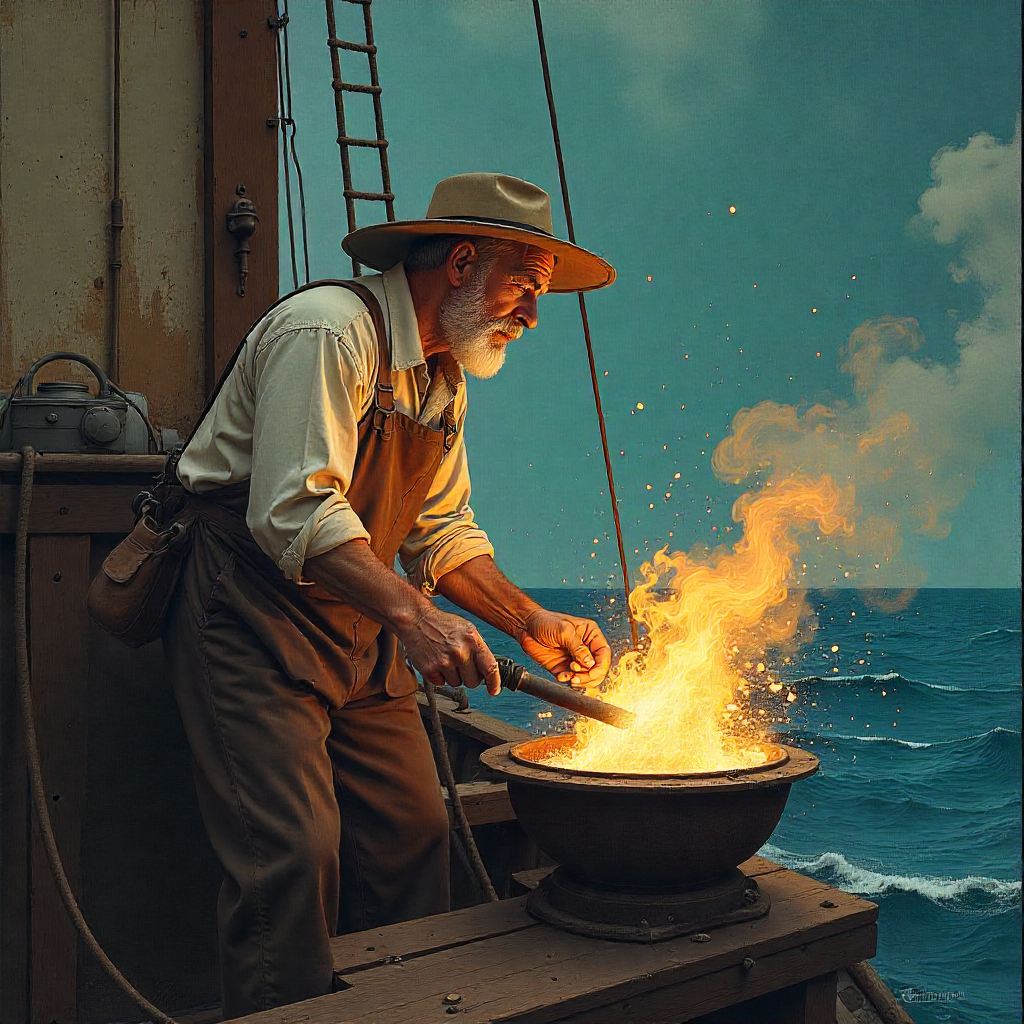

The cargo ship in On the Precipice of the Labyrinth is not a backdrop; it is a workshop where character is tempered by routine, hierarchy, and the cold arithmetic of accountability. Salt in the air, steel underfoot, and a schedule that favors necessity over romance—this is where William Benning’s purpose is ground and sharpened.

A line opens the novel like a door quietly unlatched: “It is important that I tell my story.” The voice does not hurry. It trusts time, insisting that truth requires distance and synthesis, not immediacy or spectacle. The epigraph from Miguel de Unamuno, “Suffering is the substance of life and the root of personality”, frames this ethic of patience, a reminder that character is shaped by endurance more than event.

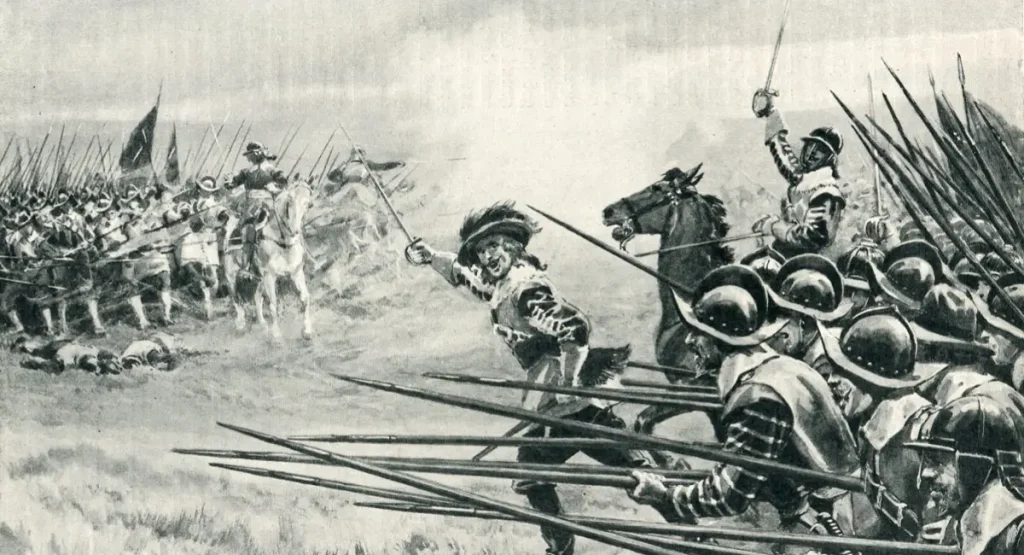

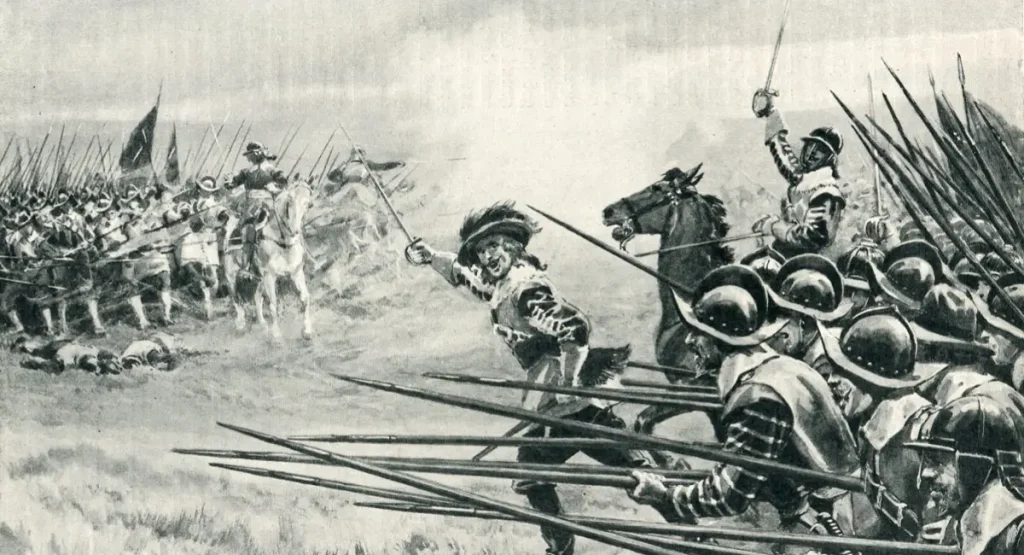

The Spanish Civil War was not just a military conflict; it was a war of beliefs that affected every aspect of life in Spain. It was a battle fought not only on the battlefields but in the hearts and minds of the Spanish people, who were divided by their political, social, and religious beliefs.

Wars have always had a devastating effect on people, but few conflicts have torn families and communities apart quite like the Spanish Civil War. Between 1936 and 1939, Spain was overcome in a war that pitted friends and family members against each other.