The cargo ship in On the Precipice of the Labyrinth is not a backdrop; it is a workshop where character is tempered by routine, hierarchy, and the cold arithmetic of accountability. Salt in the air, steel underfoot, and a schedule that favors necessity over romance—this is where William Benning’s purpose is ground and sharpened.

Cramped Quarters, Clear Edges

Before any grand horizon appears, the ship teaches scale. Space is rationed: bunks stacked close, a bed “just under six feet long” and scarcely twenty inches wide, with another bunk a foot above the face. Comfort is not the point; function is. The cabin itself reduces pretension, and that reduction becomes the first instrument of formation.

Fiefdoms at Sea

The ship’s social order operates like a chain hoist: weight distributed by rank, not sentiment. Every chief guards a “little fiefdom,” and recourse is rare. Benning’s job title—cargo mate, second class—translates into simple obedience; the education is practical and brisk. Authority is not debated; it is encountered.

Work That Names Things

Paint on lower decks. Debris cleared in waterlogged passages. The body goes where the ship requires. Yet amid the drudgery, one task stands out: counting containers in the main hold against the official manifest. Addresses, dimensions, contents—each box called and checked until the ledger aligns with reality. “Everything had to be accounted for” is more than protocol; it is a sentence about ethics, inventory as a habit of mind.

The scene narrows to the tactile and the exact: Shank calls a name or number; Benning climbs and searches; boxes range from trunk-sized to “as big as small trucks.” Work translates complexity into a series of verifications, teaching attention without fanfare.

Bodies Learn First

Formation arrives through muscle memory before philosophy. Containers can shift; vigilance prevents harm. Seasickness arrives on schedule; steadiness returns only after the body consents to the ship’s rhythm. Praise for handling the work comes in the rough vernacular of crews, not in speeches. The lesson is plain: resolve begins in the body and moves outward.

Books Behind Bars

An errand to the bursar’s office detours into a quiet exchange of culture. A tall, narrow bookcase stands behind Mr. Jenks, secured with bars so volumes will not spill in rough seas. A loaned novel—Hardy—passes from officer to crew, tracked with the same seriousness as pay envelopes. Literature here is not decoration; it is ballast, a steadying counterweight to steel and salt.

At landfall, the thread returns: rain in Le Havre, pay collected, the borrowed book returned with a wry exchange about Hardy’s tendencies. Even this minor ritual honors accountability: items borrowed, items restored, accounts settled—another echo of the manifest’s ethic.

Weather, Work, and the Choice to Continue

The ship docks under “miserable” rain; unloading continues for days; work does not pause for weather. The question then is stark: stay with the crew and the known routine, or step off into the unresolved project of Spain. The crossing has forged habits of attention and duty; those habits now power the decision to keep going.

Labor as an Ethic

The ship supplies a curriculum: hierarchy teaches humility, inventory teaches truth-telling, repetition teaches patience, and shared space teaches regard. In this light, “drudgery” becomes discipline. The cargo hold’s lists and the bursar’s ledgers make an argument about the moral life: name things correctly, return what was borrowed, accept the weather, keep the count honest.

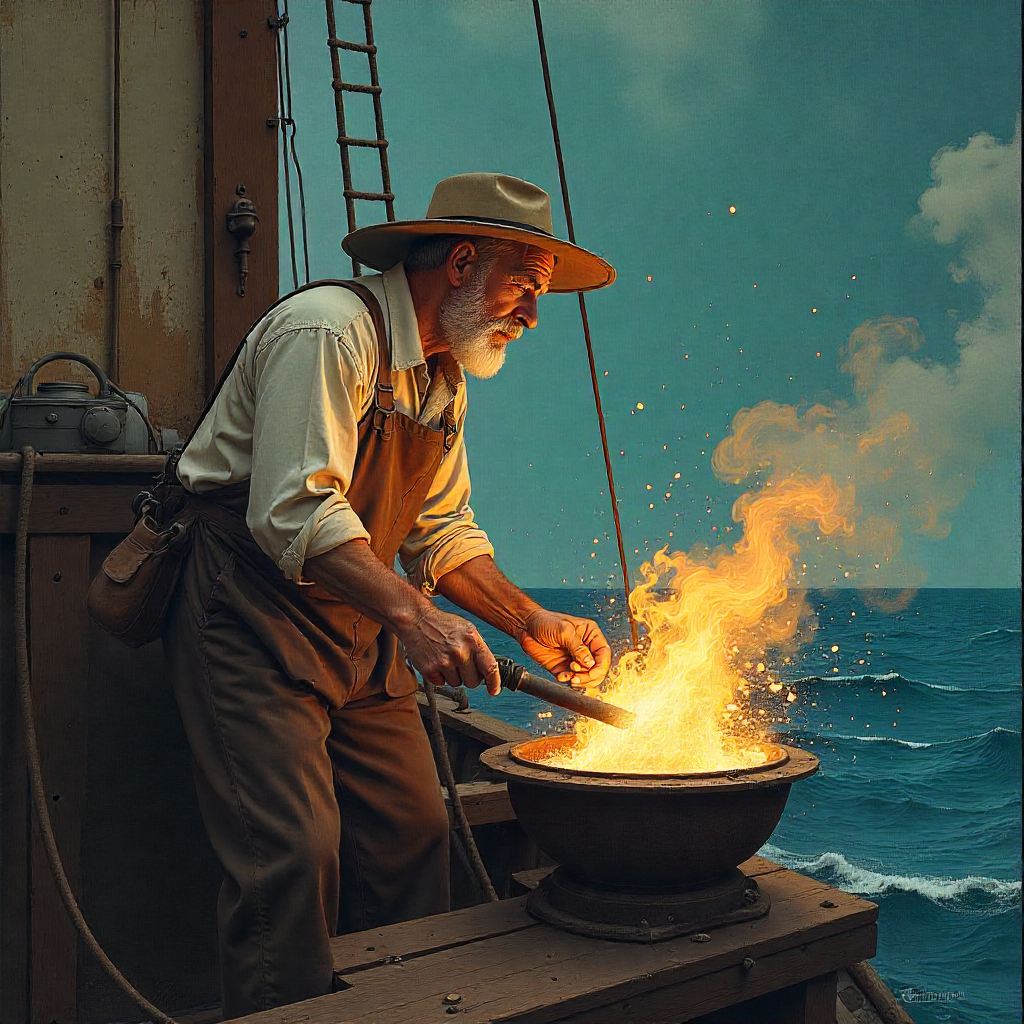

The Forge, Not the Destination

By the time Spain comes into view offstage, the ship has already done its work. Salt and steel have provided the conditions for resolve, and resolve will be necessary for witness. The voyage across the Atlantic, measured in cramped bunks, shifting loads, tally marks, and the slow exchange of a Hardy novel, becomes the novel’s moral forge—hot, exacting, and honest enough to temper a character for what lies ahead.

© Copyrights 2024 Brian Snowden. All Rights Reserved